Raising the bar without raising barriers

Artists impression of The Saplings, Timperley, Trafford. Credit: PIC Homes

Design is high on the national planning agenda. But it’s always been a hot topic in planning decision-making — often because the very idea of what constitutes “good design” is so subjective.

Sometimes it’s the outlandish examples that get attention, like Oxford’s Headington Shark or Kensington’s candy cane house. But even something as innocuous as a pink front door can cause controversy in a planning context.

It’s understandable. England’s built environment is shaped by rich heritage and strong opinions. It’s no wonder we care so deeply about design quality. In fact, the 2012 National Planning Policy Framework was clear:

Good design is a key aspect of sustainable development, is indivisible from good planning, and should contribute positively to making places better for people.

Paragraph 56 of 2012 NPPF

But if good design is essential, the question remains: who defines what “good” looks like? And does the current focus on design quality risk holding us back from the urgent task of building more homes?

Design versus delivery?

Local Blackfriars married old and new when it incorporated the historic Black Friars pub. Credit: Salboy

Housing delivery is under pressure. Planning approvals are at record lows — just 29,000 new home permissions were granted in the year to June 2025, despite ministerial soundbites calling to “Build baby build”.

But England also has one of the most discretionary planning systems in the world. Even when proposals comply with adopted policy, planning authorities still have the discretion to refuse them.

That discretion often plays out through design. And while well-designed places are worth fighting for, the tension between control and delivery is keenly felt, especially when condition discharge, committee politics or subjective opinions delay schemes that meet policy. It’s no coincidence that we also have a housing crisis. Last week the government announced it would be consulting on withdrawing or revising various design requirements from London Plan guidance to “streamline” requirements on developers. Clearly the layering of multiple design requirements is seen to be one of the factors at play in London’s stagnated housing delivery.

So, this month we’re asking: Is the planning system getting the balance right?

Designed to bring clarity

The new Cheshire Smokehouse sensitively minimised visual impact on the Green Belt. Credit: Shove Media

The latest tool in the government’s push for design quality is the design code. Introduced in 2021, alongside the National Model Design Code (NMDC) and National Design Guide, they aim to bring clarity to local expectations — and to raise the bar on quality.

If adopted as supplementary planning documents (SPDs), design codes can carry significant weight in decision-making. The goal is clear: make expectations obvious up front, speed up the planning process, and ensure consistency in design outcomes.

But are they helping?

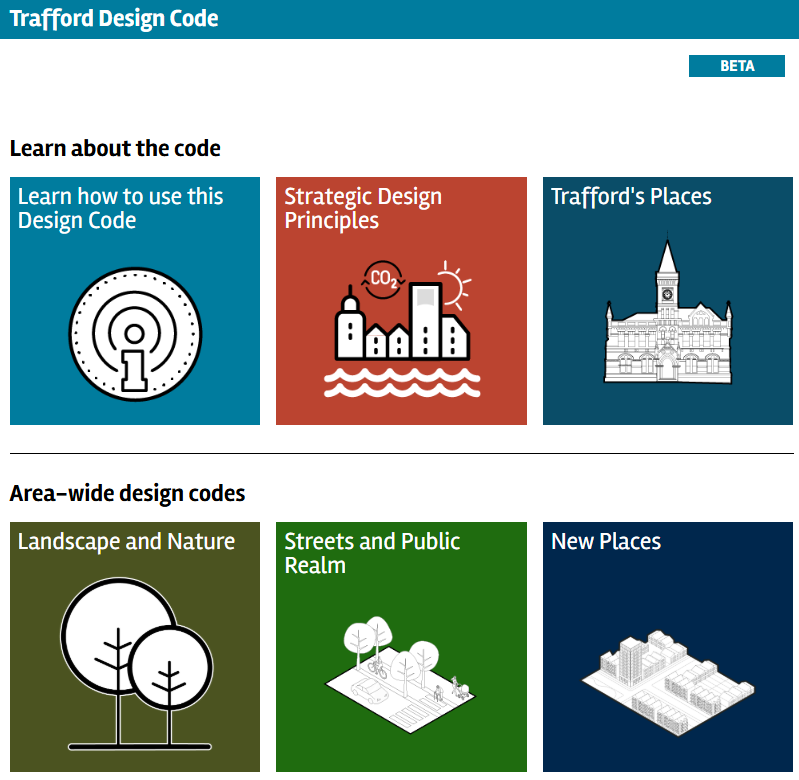

Trailblazing Trafford sets the tone

Commitment

Trafford’s work in preparing and adopting a design code has set a precedent for others to follow. One of 21 local authorities chosen by the government to prepare a design code, the borough moved quickly, adopting its code just over two years later.

This wasn’t a new approach, though. Trafford has long championed people-focused design. Citing Jan Gehl’s maxim “first life, then spaces, then buildings”, the borough’s code reinforces its commitment to quality placemaking and pride in its towns.

Clarity

Trafford’s design code is an interactive digital platform, which explains clearly how it sits within the wider planning policy context. It’s engaging and accessible, and gives stakeholders clarity over what is expected for design.

Certainty

Front loading information about its design expectations is intended to provide certainty to developers and architects, making it easier to hit the mark first time.

But is there be a better way?

Trafford’s design code shows what’s possible. But it also begs the question: are we asking design codes to do too much in a system that’s inherently discretionary?

There is another model that might be better equipped to deliver homes at scale.

Zonal planning

Excerpt from Auckland’s Unitary Plan

Unlike England’s discretionary system, zonal planning offers certainty through a rules-based approach to decision making.

Auckland, New Zealand, for example, uses a zonal approach where criteria like building height and density are fixed within defined areas. If a scheme complies, it’s approved.

Auckland’s planners recently “up-zoned” areas close to train stations, allowing for more density and new housing supply. The result? Thousands of new homes delivered — and no collapse in design quality. By and large, developers and architects are proud of their work and continue to build good quality.

Moving to a rules-based zonal system would truly bring greater certainty to the planning system and unlock potential for faster housing delivery.

Delegation by default

As we’ve said before, delegation by default — where all but the most contentious schemes are handled by officers — could reduce delays and politics. Major schemes, which often involve months of pre-app discussions and negotiation, shouldn’t always need a committee date to move forward.

More discretion at the front end, and less at the back.

If we’re sticking with design codes…

Given the current direction of travel, it’s unlikely England will overhaul its planning system anytime soon. So if we’re going to use design codes — let’s use them well.

Here’s how we think they can support, not slow down, good development:

Flexibility is key

Design codes are meant to simplify decision making through bringing clarity. But there’s a risk that they add a layer of complexity and new hurdles to overcome.

As the recent announcement regarding the London Plan’s design guidance indicates, codes should embrace flexibility to avoid becoming overly prescriptive. A window reveal measurement shouldn’t hold up 60 much-needed affordable homes.

Viability must be valued

Markets change. A design code written in 2023 may not work in 2026 when build costs, regulations and buyer demands will likely have shifted. For developers to build new homes, they need to know they’ll be able to sell them. To be effective, design codes need to be live documents — or at least written with real-world flexibility in mind.

Beware competing guidelines

Design codes don’t exist in a vacuum. Building regs change. Fire safety guidance evolves. And when codes conflict with statutory standards, confusion reigns. For design codes to be useful, they must be kept in sync with everything else developers are expected to deliver.

Feeling a little lost?

We don’t blame you. Planning has never been simple, and the design agenda adds another layer into the mix. But as Richard Roe, Corporate Director of Place at Trafford MBC says:

“Planning is the critical enabler to give certainty to development, here to set the bedrock and create the environment for quality investment to take place.”

That’s why we work collaboratively with local authorities to unlock sites and steer proposals toward consent. We’re strong believers that early engagement, grounded design thinking, and real-world pragmatism can deliver great places and hit housing targets.